Researchers have discovered that newborns have high levels of the tau protein, which is elevated in older people with Alzheimer’s disease, but that it causes them no harm. The discovery opens the door to developing new ways of treating or preventing the neurodegenerative condition.

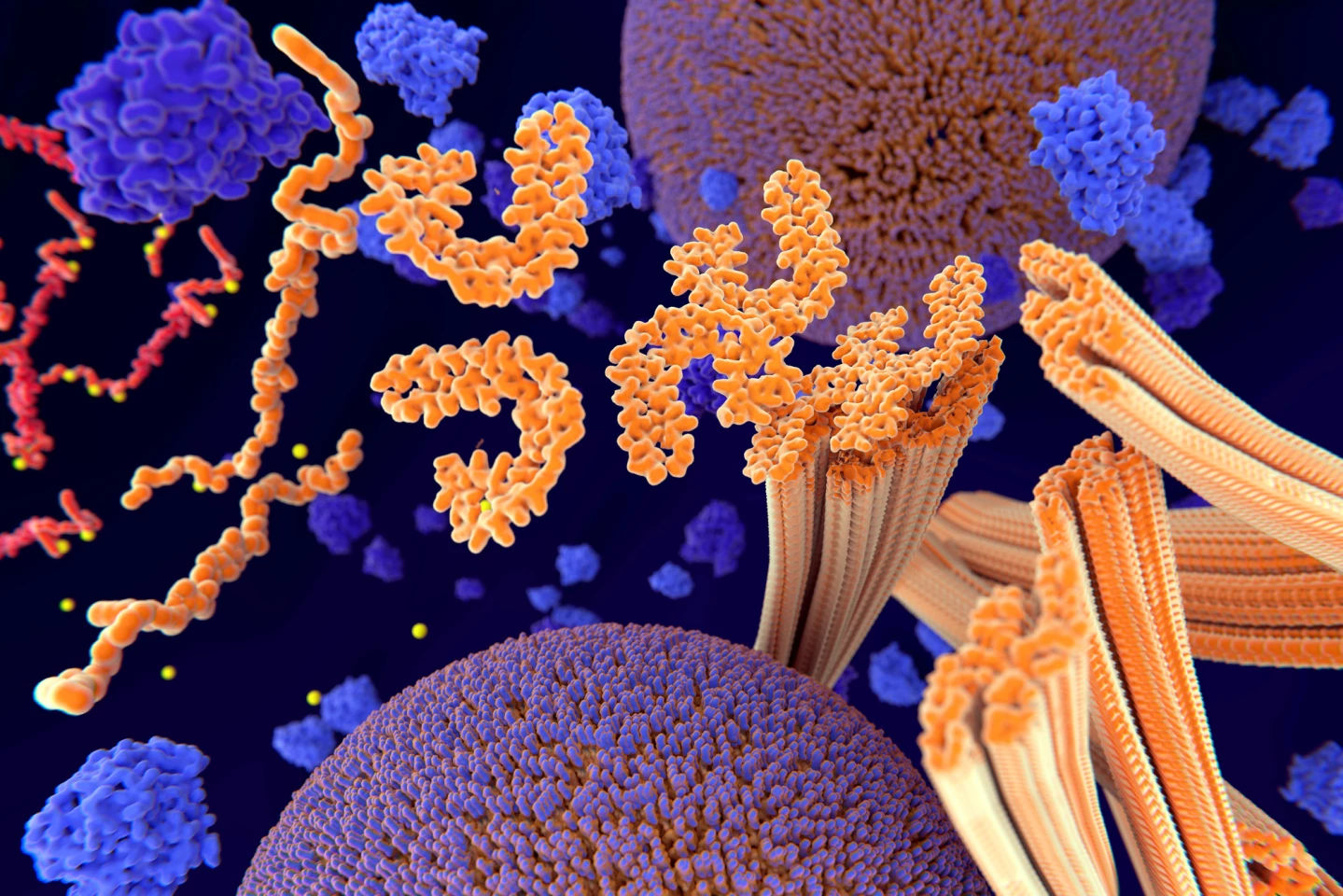

In Alzheimer’s disease, abnormal chemical changes cause the protein tau to stick to other tau molecules, which eventually form the hallmark toxic tangles that destroy neurons and the connections, or synapses, between them. More recently, tau has become an increasingly validated target for both diagnosis and treatment in Alzheimer’s research.

Now, a new international study led by researchers from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden has made a stunning finding: the elevated levels of tau seen in patients with Alzheimer’s disease are also seen in newborns. The discovery could provide a roadmap for developing new treatments for the degenerative condition.

The researchers investigated a specific form of tau, called phosphorylated tau at position 217 (p-tau217), in the blood of healthy newborns, premature infants, patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and healthy individuals of various ages. It’s the first time that p-tau217 concentrations have been measured directly in newborns. An aside: phosphorylation is when a tiny chemical group called a phosphate is added to a protein, such as tau, which is like adding a switch to change how the protein behaves. The switch can turn the protein on or off, change where it goes, and alter what it does.

In infants, p-tau217 levels were closely related to whether they were born on time or prematurely. The earlier the birth, the higher the p-tau217 level, suggesting the protein played a role in early brain development. Healthy newborns were found to have much higher levels of p-tau217 in their blood than healthy children, adults, or even people with Alzheimer’s. Indeed, p-tau217 levels in newborns were about three times higher than those in Alzheimer’s patients. In premature infants, p-tau217 levels gradually declined in the first few months of life and approached adult levels by three to four months of age.

From the study’s findings, it appeared that, in newborns, high p-tau217 levels were normal and promoted brain development without causing harmful tau aggregates. This is in contrast to people with Alzheimer’s disease, where it’s known that elevated p-tau217 contributes to the brain pathology seen in that condition.

Since p-tau217 is already used as a biomarker to detect Alzheimer’s disease, this study confirms its usefulness but also cautions that high levels are not always pathological – context matters. Understanding why newborns can tolerate high tau phosphorylation without damage to brain cells could help researchers develop treatments that mimic this protective state in older adults with Alzheimer’s. The study also opens the door to using blood-based tau markers to assess early brain health in infants, especially those born prematurely or at risk of neurodevelopmental issues.

“We believe that understanding how this natural protection works – and why we lose it as we age – could offer a roadmap for new treatments,” said lead and corresponding author Fernando Gonzalez-Ortiz, a doctoral student from the University of Gothenburg’s Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry. “If we can learn how the newborn brain keeps tau in check, we might one day mimic those processes to slow or stop Alzheimer’s in its tracks.”

The study has some important limitations. Only the premature infant group was tracked over time; there was no long-term follow-up data for other age groups. Not all study cohorts were tested for other disease-related biomarkers, like amyloid beta 42 (Aβ42) or neurofilament light chain (NfL), so cross-biomarker analysis was limited. Blood samples were tested using a single testing platform; the findings need to be verified using different assay technologies. The study couldn’t distinguish whether the tau measured in newborns came from fetal or adult versions of the protein, which may behave differently.

Nonetheless, the study’s findings suggest that tau phosphorylation isn’t inherently harmful. Indeed, during brain development, it’s vital. The key difference lies in how the brain handles tau over time. By learning from the natural tau regulation seen in newborns, researchers may discover new ways to prevent or treat Alzheimer’s disease by avoiding the pathological buildup of tau seen in aging brains.

The study was published in the journal Brain Communications.

Source: University of Gothenburg